Chlorophyll Corner: Apple - the plant that grows stories from seed

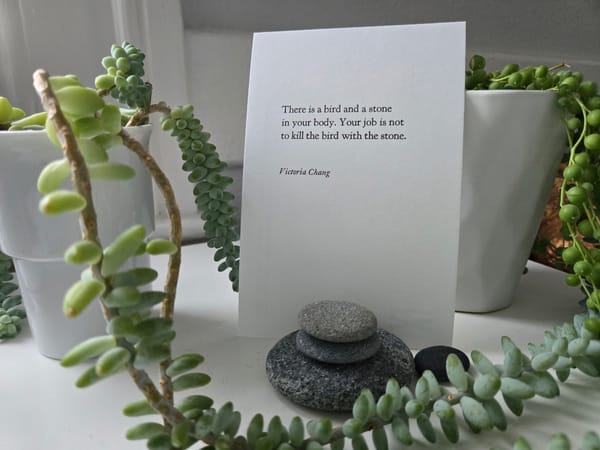

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1080"]

Photo by Eden Blooms [/caption]

A monthly ethnobotany column by Eden Blooms

As fall settles over Cascadia, the last golden rays of summer peek through the incoming overcast. The plants, environment, and human worlds have all begun their intrinsic descent through Earth's natural cycles.

The deciduous trees change their attire as we change ours. Crispy leaves fall to the ground as we pull on that familiar pair of boots and cozy sweater put away before the heat waves. Raindrops large enough to ease forest fires hit the ground in a way that sends soil and fungi into the air - making each breath more satisfying than the last.

Mushrooms popping up after rain remind us it’s time to cherish our bountiful harvests. Apples, although not native, have become a huge part of fall culture in Cascadia, producing one of our most cherished crops.

When you think about apples, where does your mind wander? Maybe to school lunches, art history, or the old saying, “an apple a day keeps the doctor away.” Maybe your senses start to remember the sensation of biting into a crisp apple or the way a warm cup of apple cider feels in your hands and excites your nostrils.

Apples are woven into our stories, some of which have been misremembered. One glowing example is how the apple represents original sin in the Bible, and yet the Hebrew word in the original texts simply meant “fruit”, not apple. This confusion speaks to how deeply apples have rooted themselves in our culture.

Washington, the nation's "apple state," grows more than half of the apples in the U.S. and exports them to over 40 countries, and yet apples aren’t native to this region or even to North America. They’re an immigrant fruit, originally from Kazakhstan, nestled between Russia and Turkmenistan. Birds and bears were the first to carry apple seeds, then humans followed, transporting them along the Silk Road as early as 1500 BCE.

When settler colonists arrived in America, they brought apple cuttings that failed in the unfamiliar soil. Only a few seeds survived, adapting to the new environment and eventually bearing fruit. At that time, apples were used medicinally for ailments like migraines and jaundice, which might have added weight to the aforementioned old saying.

Botanically, apples belong to the rose family, which is known for producing heart-shaped fruits and botanical medicine focused on the cardiovascular system. The star at the bottom of an apple is the remnant of its flower, which is designed by the plant to attract pollinators that will help aid the production of fruit. The fruit itself is a clever strategy of the plant: sweet, portable, and designed to be eaten so its seeds can travel far.

Though apples originated in Central Asia, they’ve traveled across continents and cultures, becoming a symbol of nourishment, healing, and story. Their global presence and cultural significance make them a powerful example of how plants influence, and are influenced by, human life. They remind us that human health, environmental health, and plant health are inseparable; each relies on the others to thrive.

Apples are an ideal plant to understand ethnobotany - the study of how plants shape human culture. From ancient myths to modern culture, apples reveal the deep interconnection between people and the plant world. Apples not only carry our past, but our future. In a changing climate, their resilience and adaptability remind us that survival often begins with seeds and the stories we tell about them.