Chlorophyll Corner: Queen Anne's Lace an Ethereal Weed

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1079"]

Photo by Eden Blooms [/caption]

A monthly ethnobotany column by Eden Blooms

Each summer, the roadsides and beaches of Cascadia bloom with delicate, large white round flowers that resemble lace doilies—Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), a wild member of the carrot family. Queen Anne’s lace has a way of transforming the most ordinary roadside into something ethereal; it feels like nature's embroidery dancing across the landscape. It’s no wonder this plant has inspired legends and herbal traditions for centuries.

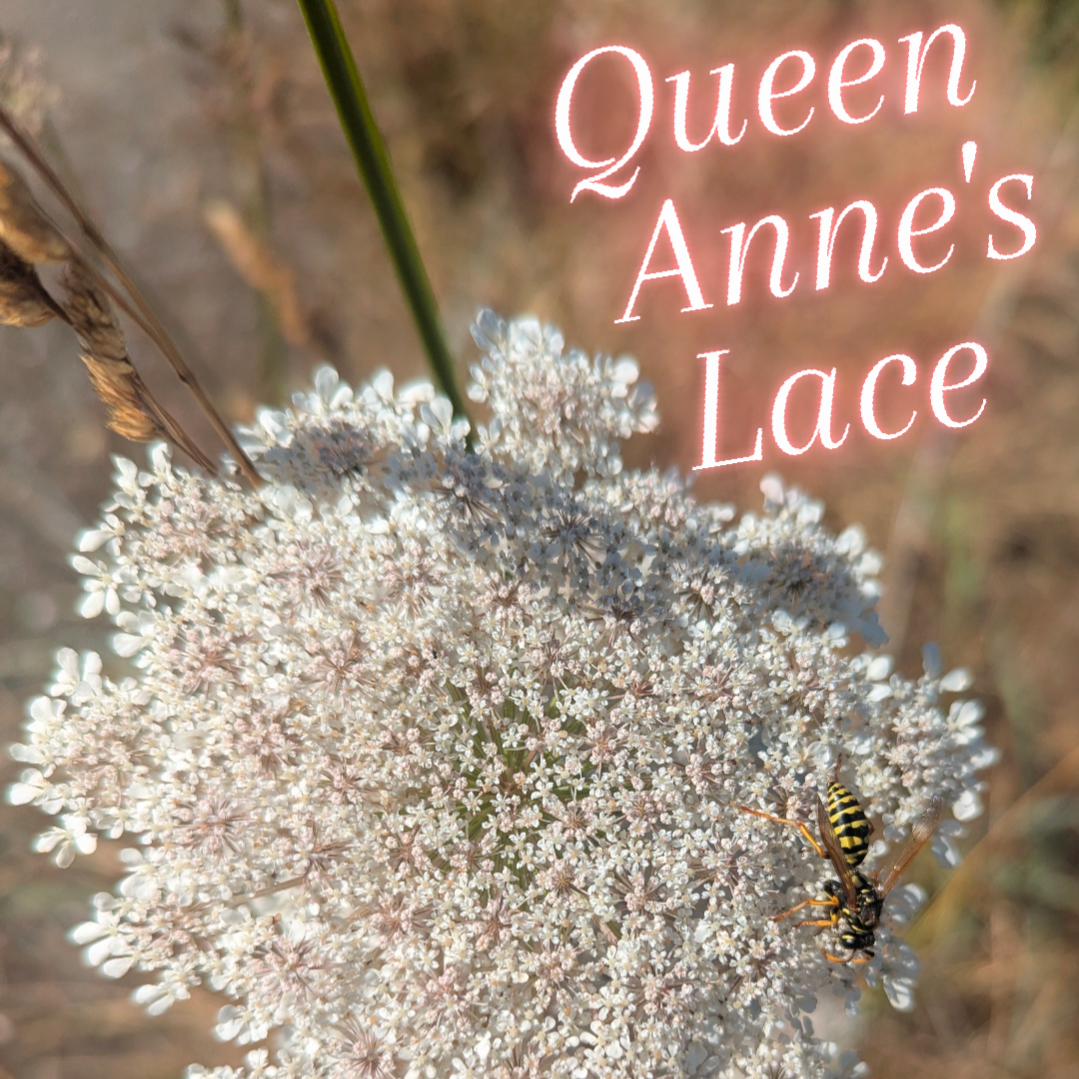

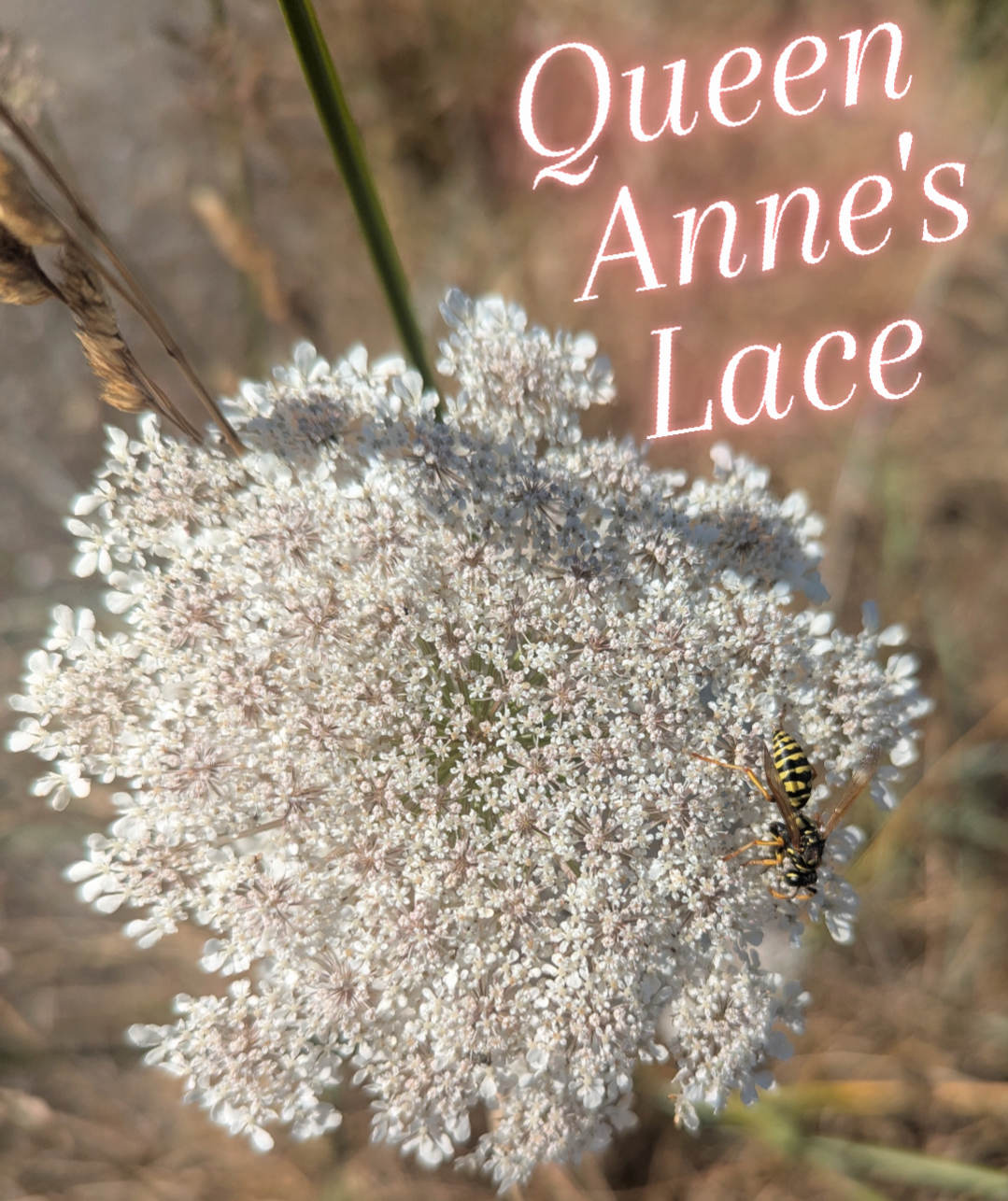

The shape of the flower is referred to as an umbel, a type of flower that consists of many small flowers spreading from a common point to form what appears to be one large flower. The stems of this plant are hairy, and the leaves are feathered and fern-like. Queen Anne’s lace grows one to four feet tall, often appearing as a biennial, meaning it takes two years to complete this plant's life cycle.

In its first year, it forms a rosette of leaves, storing starches in its taproot. During the second year, the stalks grow taller and flat-topped clusters (umbels) of tiny white flowers appear, often with a single dark purple floret at the center. Botanists have long debated this curious spot—Darwin thought it was an organ no longer in use, while others believe it mimics insects to deter predators or attract pollinators.

Queen Anne's lace is pollinated by a variety of insects, including bees, wasps, flies, beetles, and even some butterflies and moths. Once pollinated, the flower folds inward into a bird’s nest shape. By late August, the dried seed heads break off and tumble away, dispersing seeds like a miniature tumbleweed.

Despite its charm, Queen Anne’s lace is considered a noxious weed in Washington State. This plant outcompetes native grasses and can be toxic to livestock. Native to Europe, Asia, and North Africa, it thrives in disturbed areas and has become a familiar member of Cascadia’s summer landscape.

Queen Anne’s lace has been used for centuries across cultures for digestive, urinary, circulatory, and hormonal health. Its seeds, rich in volatile oils, are warming and pungent, making it a carminative which means it helps to relieve digestive cramps and gas. Herbalists often suggest adding them to meals to ease gastrointestinal discomfort. Water-based preparations like teas and infusions are common, as hot water extracts their medicinal constituents. The seeds add a mild peppery flavor while hopefully alleviating some of the predicted digestive discomfort.

As beautiful as this plant is, it comes with more than just risks to the landscape. When harvesting this plant, caution is essential! Queen Anne’s lace closely resembles poison hemlock, a deadly plant. Hemlock can cause contact dermatitis and is fatal if ingested. Never harvest these wild plants unless you’re absolutely certain of both of their identities.

Most famously in history, Queen Anne’s lace played a role in reproductive health. Ancient Greeks, including Hippocrates, used crushed seeds as a contraceptive. Herbalists in Appalachia and Europe continued this practice, and some modern herbalists still investigate this plant's potential. Some studies suggest it may interfere with progesterone, preventing egg implantation, but results vary, and safety is not guaranteed. Because of its contraceptive potential, this plant should not be ingested if pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

In light of recent rollbacks on reproductive rights, including access to contraception and abortion, Queen Anne’s lace’s legacy as a folk contraceptive raises pressing questions. Should people have to rely on under-researched plants for reproductive autonomy? While its use is historically significant, it’s not a substitute for safe, evidence-based healthcare.