Citizen Screen: Do Film Festivals Have the Answer?

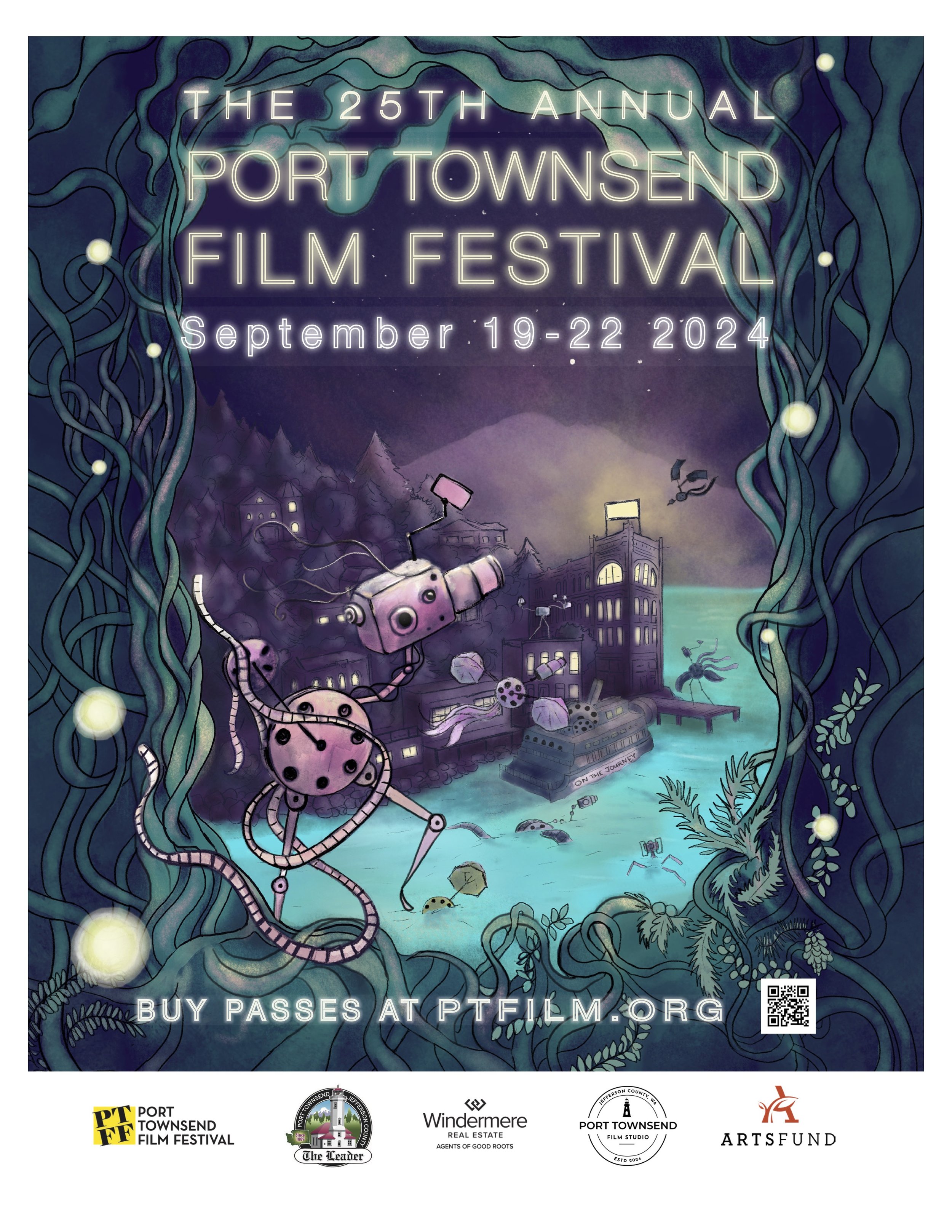

[caption id align="alignnone" width="2550"]

PTFF Poster by Michelle Hagewood [/caption]

Citizen Screen is a monthly column dedicated to film and film-related topics, sourced and curated by Port Townsend Film Festival. This month’s column is by Danielle McClelland (they/them). Danni is the Executive Director of the Port Townsend Film Festival; founder of the PRIDE Film Festival, Bloomington, IN; and in their occasional spare time, a writer/director/performer with a penchant for large-scale puppetry.

Film festivals the world over appeal to audiences as both a way to experience films they might not be able to ever see any other way and to see and be seen with the people who populate the news feeds of our every day. In some ways, we’re attracted to the novel. In other ways, we’re seeking association with the rare, but well known.

At the community film festival level (like what we have here in Port Townsend), the event is also about community involvement, volunteerism, and the impact of bringing new ideas and new people into the conversation a town is having about itself and the world around it.

For filmmakers, though, the festival has traditionally been a cultural gatekeeper and the determining factor in their potential success. The rags-to-riches promise of getting into one of the elite festivals and getting a big distribution or streaming deal is the dream most filmmakers are chasing. It is also the primary way most burgeoning filmmakers are planning to recoup the money they and their investors poured into their project.

Yet, the possibility of this dream becoming reality has always been slim at best, and according to many, it is becoming even more rare.

Isabelle Huppert, veteran French actress and this year’s president of the Venice Film Festival jury, when questioned by the New York Times last month, reasserted the primacy of film festivals. “Festivals are more and more important. We all know that with the development of new ways of watching movies, such as streaming platforms - which do have their virtues - movie theaters are somewhat threatened. So festivals are crucial ecosystems for the visibility of movies and for the film industry as a whole.”

Others are more skeptical about the possibility of the elite film festival making someone’s career. Amy Hobby, an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning veteran independent film producer, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her 2015 What Happened, Miss Simone?, has been outspoken about the ways in which the film festival model does not necessarily work to encourage innovation or welcome new voices. “If you’re one of 5% or less that get into one of the A-list festivals, then you have less than that percent to sell your film at that festival. It’s not a business strategy. There needs to be a huge mind shift around why we go to festivals and what sort of festivals we choose to premiere at, or if we need festivals at all. It’s not for every film.”

Hobby made these statements in February as part of the podcast Distribution Advocates. Premiering its first episode in January of 2024, Distribution Advocates describes their mission as “work[ing] to collectively reclaim power for independent storytellers in the current systems of distribution and exhibition, fight[ing] for radical transparency, rebalancing entrenched inequities, and blazing a new, more interesting, accessible and inclusive way forward.”

In the same episode, Jemma Desai, a programmer, researcher, and writer based in London, brings a particularly blunt characterization of the film festival to the forefront.

“There’s a lot of colonial language in the film festival and in the idea of distribution, and there’s a lot of ideas of extracting, of exploring, so I think it’s really interesting that the presentation of the film festival is this idea of hospitality and guests, but actually, when the business is done, it’s all about exploitation. It’s all about territories and rights, and it’s very law-like language. There’s this clash. You’re attracted to this neoliberal idea of hospitality, but actually, what’s happening is that you’ll only be needed if you can be exploited.”

While A-list film festivals may be struggling with (or actively ignoring) these very real critiques, it’s possible for the smaller festivals, where access to distributors has never been a factor, to brush off these issues, thinking they don’t apply to them. Desai asks a particularly relevant question, though, which all cultural presenters should be asking themselves and their communities. “What do we want from each other after we have told our stories?”

When we work to build community through film, this question goes to the core. Is the typical Q&A with the director following the screening of the film truly satisfying for the director or the audience? If it’s good, could it be better? Could something else be even better than that? As filmmakers what do we want from our audience other than the support - emotional and financial - to make our next film?

For small town film festivals, the act of buying and selling national distribution rights is not a circumstance we are generally involved in. We are, however, uniquely positioned to experiment and innovate in the realm of the conversation the film elicits and how far the impact of that conversation goes. Without the pressure of big deals, small festivals might just be the circumstance in which artists and audiences can really communicate with one another. In a world where there is an increasing gap between the tens of thousands of worthy films created each year and the larger, but still extremely limited, variety of films available in theaters and streaming services, the small-town festival just may be the place where we can figure out what we can give each other after we’ve told our stories.

We look forward to exploring a variety of film and film-related topics in the months to come. Want to propose a topic? Send your thoughts to: info@ptfilm.org.