County and Local Partners Exploring Solutions to Failing Chimacum Watershed Management

[caption id align="alignnone" width="4032"]

Clearing the Canary Grass out of Chimacum. Photo courtesy of the Jefferson County Conservation District. [/caption]

News by Scott France

Heading south from Chimacum on either Center road or Highway 19, travelers are treated to bucolic landscapes that suggest healthy streams, and fertile, productive forest and farmland. But under this surface, the actual health of these Chimacum Creek valleys is more tenuous than it might appear.

The days when Chimacum Creek supported thriving runs of coho and chum, salmon, steelhead and trout are a distant memory. A proliferation of reed canarygrass has blocked water flows into waterways, causing flooding on hundreds of acres of once highly productive farmland. The grass was introduced as forage for cattle, but now there are few, if any, cattle in the watershed. It can reach heights of over six feet and form mats of rhizomes, stems and leaves across streams and ditches, choking the flow of water and creating challenges for adult and juvenile fish migration. It also robs the water of oxygen as it decomposes, resulting in lethal conditions for fish. In many areas, seasonal flooding now extends well into the growing season.

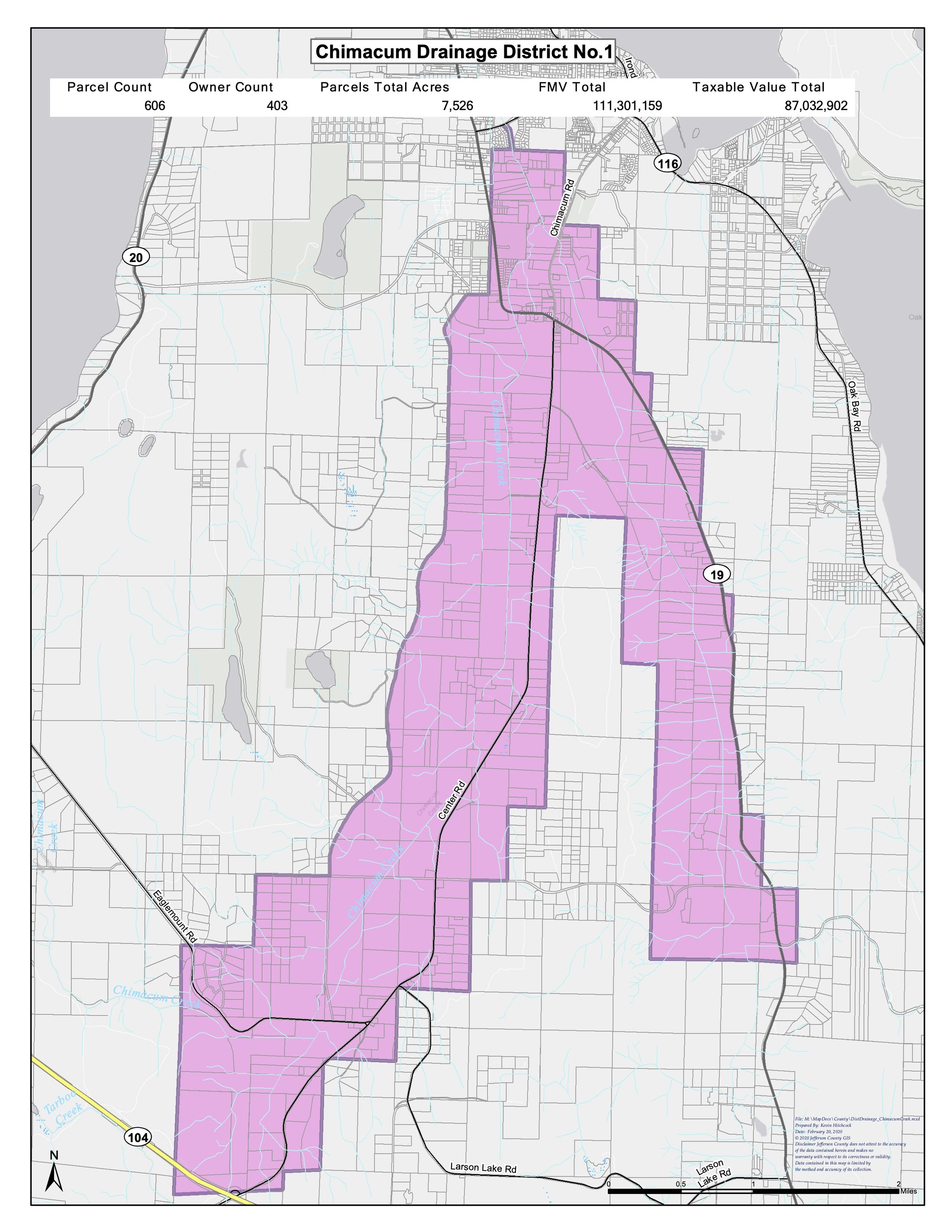

[caption id align="alignnone" width="2550"]

Image courtesy of the Jefferson County Conservation District. [/caption]

The Jefferson County Conservation District (JCCD), in collaboration with local agencies, farmers, and other landowners, is developing a comprehensive drainage management and improvement plan for the Chimacum Creek watershed. This plan aims to balance agricultural needs with ecological restoration, considering strategies such as reactivating the drainage district, creating a new management entity, or continuing with individual landowner maintenance.

Joe Holtrop, manager of the Jefferson County Conservation District (JCCD), brought years of experience to the table as the parties convened to discuss the problems and potential solutions. He worked at the district in the early 90s, then worked for 30 years with the Clallam Conservation District, before returning to JCCD. “When I came here in 2021, drainage and flooding was issue number one,” Holtrop said. “We (the Conservation District) don’t have the authority to direct the needed changes, but we can provide technical assistance to those who want it.” Holtrop says that removing the red canarygrass from the steam channel is a top priority.

The main branch of Chimacum Creek runs parallel to Center Road and is commonly referred to as West Chimacum Creek, while East Chimacum Creek roughly parallels Highway 19. Agriculture thrived in these valleys for just a generation or two following major alterations in the natural drainage system, including channelization of Chimacum Creek, excavation of many miles of drainage ditches, and installation of miles of subsurface drainage. The vast majority of the drainage system alterations were undertaken by the Chimacum Drainage District, which was created in 1919, but has been dormant since 1974.

The grass problem is compounded by native plants and trees that were planted alongside the creek for the past 30 years, according to Eric Kingfisher, Director of Stewardship and Resilience with the Jefferson County Land Trust. JCCD and the North Olympic Salmon Coalition started these plantings 30 years ago to provide shade and better habitat for the stream, while Holtrop was at JCCD. “ Unfortunately, these plantings, especially the ones with a lot of willow, attracted beaver,” Holtrop said. “ They moved in, ate plantings and built dams, which resulted in more flooding, sometimes drowning many acres of established riparian plantings.”

Most land owners struggle to care for and maintain these trees and plants, and removal has occurred sporadically over the past three decades, and removal of sediment has not occurred because of permitting challenges. Sediment tends to build up in the channel due to a lack of velocity from low gradient and reed canarygrass choking the flow.

Most reed canarygrass removal has been limited to a handful of properties, as it has been largely paid for or performed by individual landowners. However, in 2020, JCCD received grant funding from the Washington State Conservation Commission to provide cost-share assistance for its removal. Five miles of stream channel across 14 properties was cleared of the grass with an excavator attachment specially designed for removing reed canarygrass. The project successfully improved stream flow and reduced flooding; however, one year after the treatment, the grass was growing back into the stream channel.

Deciding on an Action Plan

When Heidi Eisenhour started looking into the watershed problems during her first term as a Jefferson County commissioner in 2020 through multiple meetings, surveys and focus groups with area residents, she and the other commissioners gained a deeper understanding of the problems and the effects on the farms, ecology and land owners, and that the uncoordinated care and maintenance dramatically altered the watershed’s natural processes. “A healthy majority of the residents of the Chimacum Drainage District who responded to our March survey were supportive of developing a coordinated plan,” she said.

Partners such as Holtrop, who had dived deeply into the issues, reinforce Eisenhour’s findings. “This is a completely dysfunctional system,” he said. “ It’s not good for the farmers and the public and it’s not good environmentally.”

[caption id align="alignnone" width="2092"]

Image courtesy of the Jefferson County Conservation District. [/caption]

So while there is a consensus among stakeholders and agencies around a goal to identify and detail management and maintenance practice and special projects that will help reduce flooding impacts to farmland, while also improving water quality and habitat conditions, the path to planning, implementing, funding and executing is complicated.

The degree to which landowners are currently affected and would benefit from certain solutions varies widely, presenting a challenge to fairly appropriating financial responsibility. Kingfisher acknowledges this challenge, and both he and Eisenhower float the possibility of a tiered system of taxation, where landowners who would benefit most would be assessed a higher tax amount than others. Kingfisher cites “the systemwide nature of the problem,” and the value that a healthy system has not only for farms, but for all land owners. “While one farm floods, the source of the problem could be four or five farms away,” he said. ”We need to be thinking long-term about working together to prepare for hotter summers, and warmer, wetter winters.”

Reactivation of the drainage district is the most commonly discussed solution. Eisenhour will meet with the Conservation District on May 13 to determine the feasibility of its reactivation. Alternatively, a New flood control District zone or possibly Watershed Improvement District might be formed according to Holtrop and Eisenhour. A third, and apparently less desired approach, would be the continued management of the system by individual landowners.