Disability Pride Month: Envisioning a World That Can Hold Us ALL

Opinion by AJ Hawkins

My “disability pride” isn’t always intuitive to my healthy peers. People often think of the disabled as pitiful bodies of burden, or infantilized objects of inspiration (if they even think of us at all). To be fair, sickness and disability weren’t part of the story I had imagined for myself, and certainly not as the dominant theme of my twenties.

When I understood myself as “disabled” for the first time, it felt like stepping off the cliff of my own self-concept. What I found down the rabbit hole was a community, a history, and a culture that didn’t just offer me a new way of understanding the world and myself—it demanded it. It’s in my disabled identity that I find a nourishing joy, hope, and orienting rage for surviving these apocalyptic times that the able-bodied world seems to lack. (Do I dare call it deficient?) My wish this Disability Pride Month is that disabled joy—and disabled wisdom—will be catching.

Disability is everywhere, we just don’t often see it. More than 1 in 4 Americans has a disability—it’s just not 1 in 4 Americans who identify as disabled. There’s a big difference between accepting your diagnosis as a medical quality and embracing disability as a sociopolitical identity. When you finally do, you understand yourself as part of the collective—your unique, individual experience as a thread in the universal human tapestry.

The magic of the disabled community is that we’re the largest and most diverse marginalized class. We embody every intersection. Disability is natural, and humans are temporarily able-bodied at best. Whether through illness, accident, or the day-to-day wear-and-tear of enduring capitalism—your body will fail. You will be disabled if you have the privilege to live long enough. The myth of the able-bodied community is that we’re distinct at all.

This myth has real roots: disabled history is defined by segregation. My disabled ancestors survived the institutions, freak shows, and Ugly Laws. (These laws made existing in public in a disabled body a crime, and the last of which was overturned in 1974.) In March of 1990, disabled activists abandoned their wheelchairs and crawled up the U.S. Capitol steps to pressure reluctant lawmakers to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act. This was the only way into the Capitol building at the time. Today, my disabled kin spend their school years separated from able-bodied peers. They spend their adulthoods doing the same—excluded by inaccessible systems and architecture, and the nostalgia for normalcy in an ongoing pandemic. This segregation perpetuates the invisibility of disabled people, and our civil rights issues, even within self-identified “inclusive” spaces.

Since the election, I see a lot of people afraid to lose their rights: from marriage equality to bodily autonomy to existing safely in the public sphere. While I see care and concern among my disabled friends, I don’t see the same kind of shock and despair.

For the disabled community, these rights can’t be taken away because we’ve never had them. We often have to choose between marrying the person we love and the healthcare we need to survive. In 31 states, we can be forcibly sterilized. We are exempt from the minimum wage, and can be denied our right to vote. For disabled folks, these are not new fears—these are old fights. We continue on as we’ve always done.

As bodies of exclusion, it’s on the margins where we build our homes, grow our gardens, and invent new ways of thriving outside of systems that don’t even want us to survive. When you start to process the world through the language of access, you begin to see what—and who—is missing. Safety nets look more like sieves, designed to catch some while allowing the undesirables to fall through.

Disability justice asks us to envision a world that can hold us all. It defies our capitalist understandings of time, labor, and the fundamental value of a person. (One of the biggest tasks of unlearning ableism is relearning our own worth.) Disability justice queers our brains, bodies, movement, relationships, and pleasure. From the outside, you don’t just see the shape of things as they are, you start to see how many other ways they could be.

Meeting needs in an inaccessible world requires a kind of interdependence, resilience, creativity, and grit that reimagines everything from how you enter a building to how you define your family. When we abandon ideas of normativity and center the needs of those most affected, equity is the consequence and community care is the conduit. This adaptive skill set makes community organizing, mutual aid, invention, and liberatory activism the strengths of the disabled and core components of crip culture. It means that the tools for surviving these dark times are already all around me—and you, too.

To me, that feels like pride. To me, that feels like hope.

If you are someone who faces the future with fear and uncertainty, if you are new to organizing or activism, the hope I have that I share with you is this: There is a playbook. There is lived expertise. There is intergenerational wisdom that already exists. You don’t have to build the path; listen and follow. If you don’t already—support disabled activists, artists, and educators. If you’re unsure where to start—watch Crip Camp and look to the work of folks like Sins Invalid, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, and Johanna Hedva. If you don’t have disabled friends—figure out why. Come by KALMA and introduce yourself; I could be your first one.

My deep belief is that the solutions to surviving this administration (and creating a world that exceeds the one that came before it) lie in the minds of disabled bodies. My deep hope is that able-bodied folks will grapple with what they deny themselves when they maintain the status quo of our segregation, and embrace allyship to us and their future-disabled-selves.

In the meantime, we the disabled will continue to organize—around the world, across the internet, from our beds, and in this our small hometown—to build a more imaginative, liberated, and accessible future for us all.

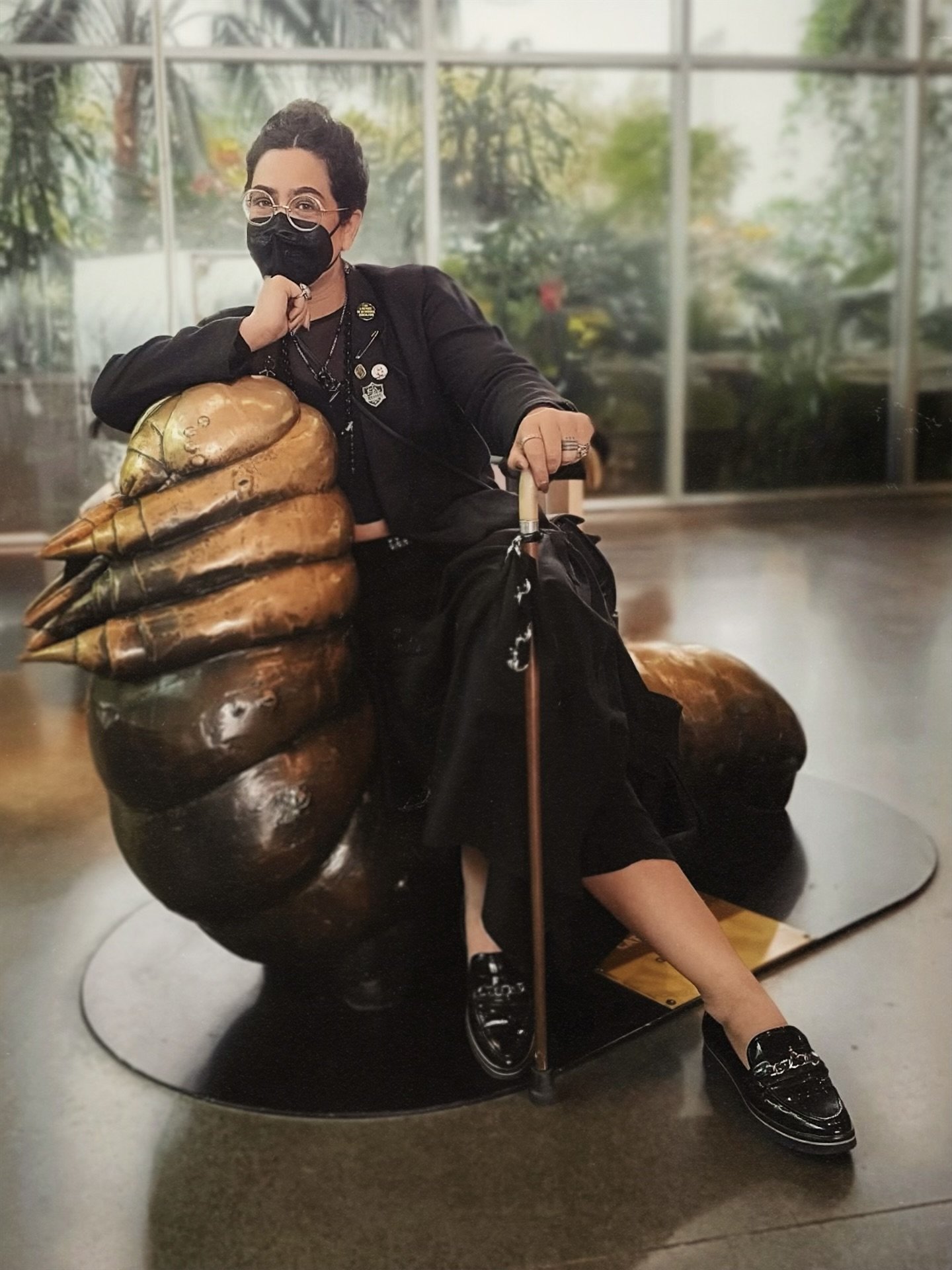

AJ Hawkins (she/they) is a disabled deathworker, friendly goth, and disciple of decay. She is the Founder and Creative Director of KALMA, a death positive retail storefront offering curious goods for self-care and self-expression, and The Parlor, a third space project weaving community at the intersections of grief and joy.