EFM Secures Major Carbon Credit Agreement with Microsoft, Aims for Enhanced Forest Health and Economic Viability

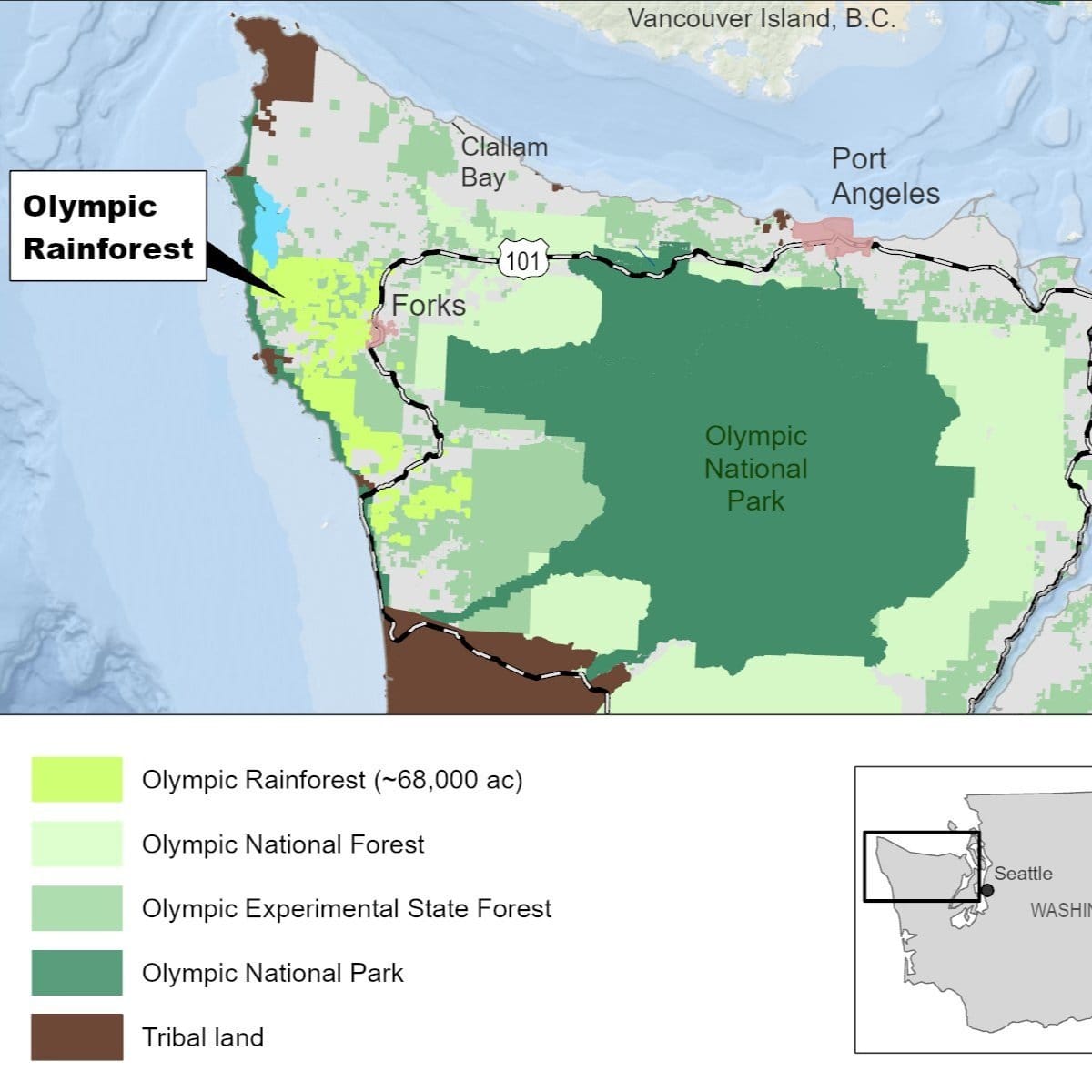

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1463"]

The property that EFM manages and Microsoft has invested in is the Olympic Rainforest, a 68,000 acre property that spance Clallam and Jefferson Counties. Image provided by EFM [/caption]

News by Nhatt Nichols

“To participate in the carbon credit market, you really have to be doing something that's above and beyond what would be happening anyway without your project. In this particular case, we have acquired a 68,000-acre forest, 31,000 acres of which is in Jefferson County,” Bettina von Hagen said in an interview about their latest project, an agreement with Microsoft that, along with a fund investment, secures 3 million nature-based carbon removal credits.

Von Hagen, the CEO of EFM, a Portland, Oregon, forest investment and management firm, has been finding ways to preserve and improve carbon-rich forests and give companies like Microsoft the opportunity to invest in carbon offset credits.

[caption id align="alignnone" width="2000"]

Photo courtesy of EFM [/caption]

“Our goal is to increase long-term forest health, and also the long-term economic value of the forest,” Von Hagen said. “Carbon financing is one of the tools to help us get to our desired future condition for this forest, which is a forest with more carbon sequestration and enhanced habitat.”

The carbon credits that EFM creates are based on the amount that they can improve a forest’s natural carbon retention above its normal, baseline amount. They do this by managing the forest to contain trees that are at their peak ability to sequester carbon, meaning that they are between 70 and 100 years old.

EFM removes trees that are no longer able to sequester carbon efficiently, mostly using thinning techniques to remove trees that are defective in some way; they’re overcrowded or competing for resources with other trees. By doing this, they’re able to accelerate the growth of a tree stand.

“Thinning is a technique we use wherever that's possible. Where it's not feasible, we use something called variable retention harvest, which is a terminal cut, but we're retaining trees in the harvest unit. A lot of times we retain those around riparian areas, sleep slopes or other important features,” Von Hagen said.

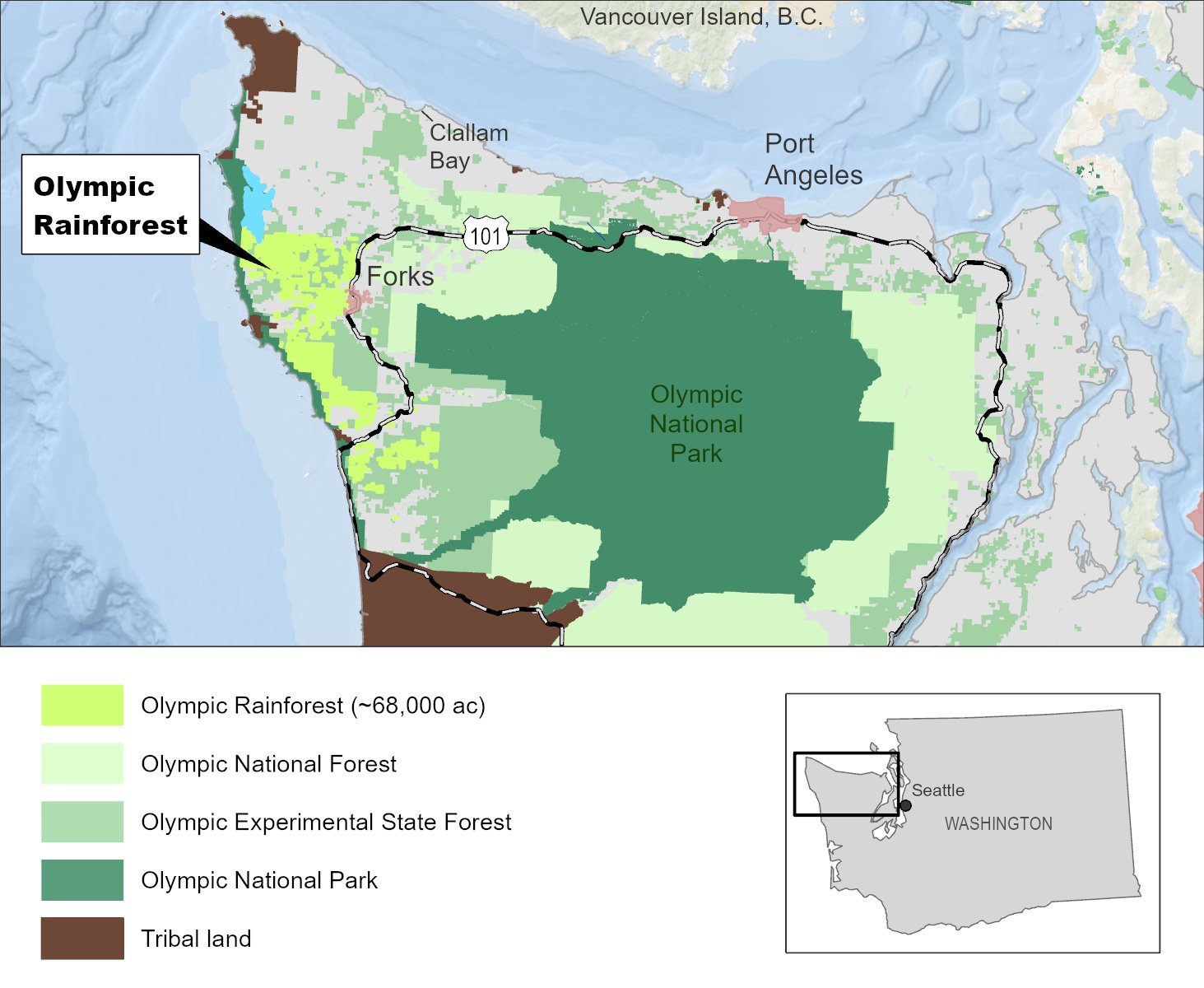

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1512"]

Timber from the Olympic Rainforest heading to the mill [/caption]

Von Hagen acknowledges that it’s a delicate balance between protecting forests and creating a functional economic model.

“We're investing in the long term viability of the forest products industry in the region by ensuring that the volumes and the quality are there to sustain the industry, while at the same time, we're doing that from a base of sort of higher carbon storage and a forest that is more structurally complex, that has species diversity, that has all the pieces, that has understory, and is a forest that is richer in carbon, richer in habitat and a richer recreational experience. So that's the sort of sweet spot that we're aspiring to,” Van Hagen said.

One major difference between EFM and Rayonier, which owned the forest before EFM purchased it, is that they encourage recreation on their land. This particular parcel is located on the west side of the Olympics, and they are already working with Clallam County to include sections of the Olympic Discovery Trail.

Beyond carbon credits and selective timber harvests, EFM is always interested in finding other ways to increase profitability without increasing impact on the environment.

“Non-timber forest product harvesting is also an important component. It is obviously not as large as timber, but we have very active leases for salal,” Von Hagen said. “It employs a lot of women, which is really interesting for us, because otherwise, for other forest activities, there are fewer women who participate in traditional timber activities.”

Von Hagen invites people who would like to find ways to develop non-timber forest products, like salal berry jams, spruce tip cider, or foraged mushrooms, to reach out to EFM with their ideas.