Navigating The Next Pandemic: Community Resources For Public Health Challenges

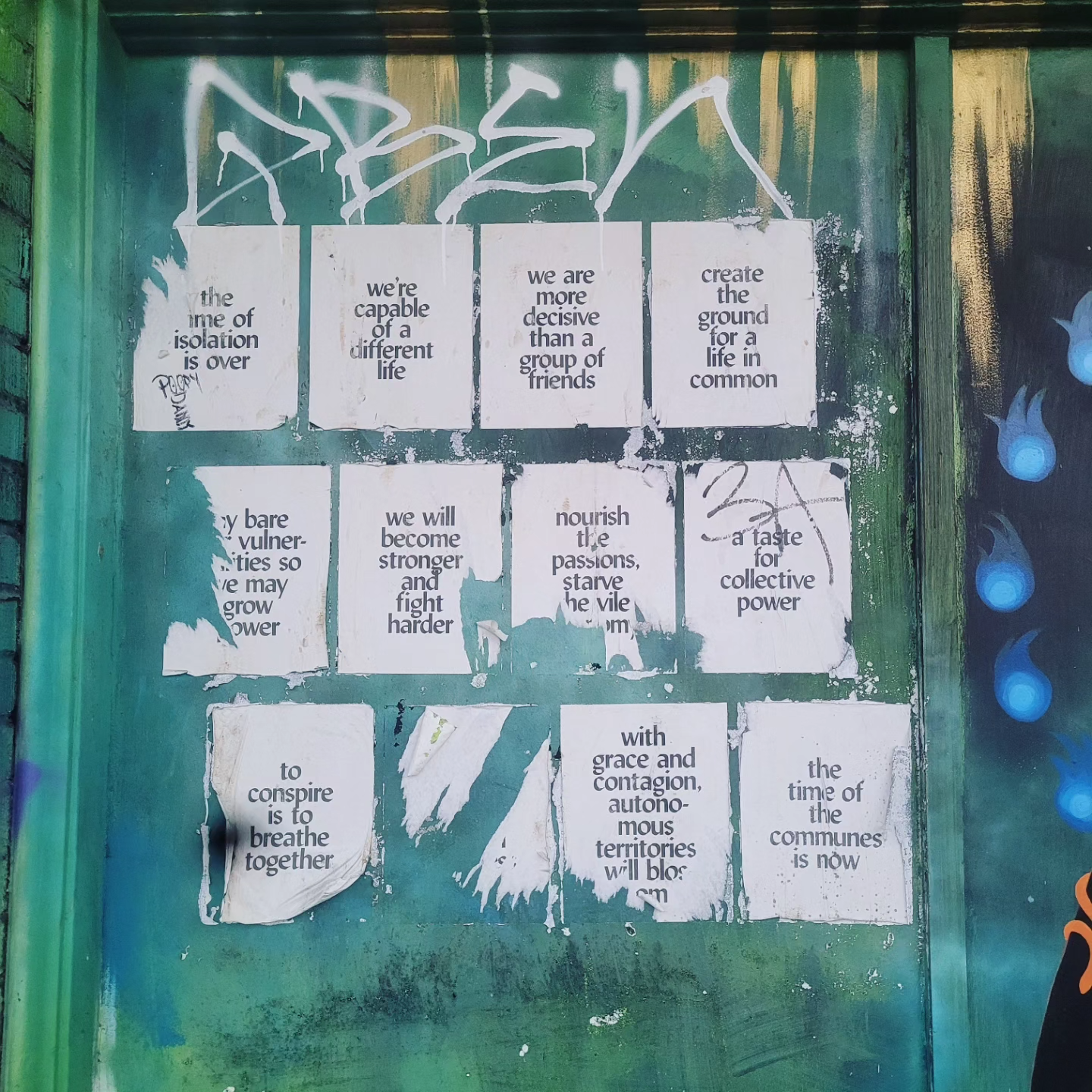

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1440"]

Community is a key part of rural health. Photo by Sara Post. [/caption]

By Sara Post

As local and global crises continue to affect each of us individually and collectively, there are few things more universally daunting than the possibility of another global pandemic. A pandemic presents both danger to the body as well as to the infrastructures we have to hold it – infrastructure which is already weakened by the toll of Covid-19.

In Jefferson County, the Public Health Department keeps a close eye on emerging viral and bacterial borne illnesses through their Communicable Disease Prevention Program. Each time certain dangerous pathogens reach the attention of epidemiologists, systems are put in place to try and prevent their spread. For example, in the case of H1N1 (also known as Avian Bird Flu), Jeff Co Public Health writes a series of recommendations published online. These recommendations are shared at Board of Health meetings monthly, along with reports from the clinics and hospitals as needed. And you can track the spread of infectious disease in the emergency room and inpatient units through the WA RHINO website- a public reporting interface on symptomatic and non-symptomatic cases of communicable illness.

But there are larger questions at play; such as, how do we trust that the CDC or that WA Department of Health recommendations are accurate and sufficient to protect those most affected by a pandemic? How can we take lessons from Covid-19 response on an individual, community, and systemic level to inform our approach? How do we build stronger local networks to collectively tackle future health challenges unique to our area?

It helps to understand the major healthcare infrastructure that currently exists so that we can understand where to fill in the gaps, as well as how to hold it accountable.

Jefferson Healthcare is a Public Hospital District, with a publicly elected, 5-person Board of Directors. It has numerous clinics as well as a hospital that qualifies as a Critical Access Hospital (CAH) because of its location in a rural area greater than 35 miles from another hospital and its provision of essential services, including 24-hour emergency care.

As the only hospital in the county, Jefferson Healthcare has the only inpatient beds needed in case of another serious pandemic. But because of its small size, a large influx of patients would quickly overwhelm its capacity.

Beyond healthcare institutional and public health infrastructure, Jefferson County consists of overlapping rings of community networks. Local farmer, food producer, and former librarian Turner Masland balances formal and informal networks to source health information. “For example- in the case of the recent H1N1 worries, my primary is face to face– interacting with neighbors. Because we sell at farmers’ markets, there is a lot of communication that happens there. And then there are some trusted listservs, such as the WSU extension office newsletter, and the Jefferson Grower’s network,” Masland said.

Masland cites the recent outbreak of monkeypox as a time in which he relied on informal networks for up-to-date information: “This [disease] primarily affected queer men. It was very hard to get a vaccine locally. The easiest option was to go to Seattle. So I talked to other members of the queer community to see where people were getting the vaccine- they had the best information. Though, if I still had questions, I would go to the health experts.”

He explains that some of his approach to sharing health information is inspired from the AIDS epidemic– “it didn’t affect me personally, but it affected the generation just ahead of me. Seeing a model where an entire community was ignored until they organized and took direct action. I’m not saying that with H1N1 we’re at that level. But, I am definitely thinking about what the next few years could look like. Knowing how the Trump administration already demonizes vulnerable communities, going forward I’m always going to be reaching out to folks that I know personally just to have a conversation about public health issues. This is all part of community care.”

There are countless examples in history of how people build networks of trust and share health information. For those interested in participating in formal health infrastructure, the Jefferson County Board of Health is currently seeking applicants for the “consumer of public health” position, defined as a county resident who self-identifies as having faced significant health inequities or as having lived experiences with public health-related programs. For those wanting to tap more deeply into informal networks, we could take a leaf out of Masland’s book and keep sharing health resources with our neighbors. Sometimes, between both means, we will find trustworthy perspectives that allow us to face the challenges as they continue to be presented.