Of Hearts and Heros – a new era for the Silverwater Café

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1080"]

A mosaic made from pieces of the handthrown plates made by David Hero for the original Silverwater location is part of the decor. Photo by Kathie Meyer [/caption]

News by Kathie Meyer

When Alison Hero, 61, posted on social media her gratitude for all of her years spent, 36 of them, with David Hero, 76, and the Port Townsend community at the Silverwater Café, the changing of the guard at one of the city’s most beloved restaurants was at last somehow official.

“And it [is] with a full heart that I can write these words,” she wrote.

That, simply, is the summation of the Heros’ philosophy: do it with a full heart.

[caption id align="alignnone" width="486"]

Rosscoe Bryant has no radical plans for changing the restaurant he recently purchased. He likens it to buying a classic, restored car. All of the hard work is already done. Photo by Kathie Meyer [/caption]

“You put your heart into it as if you’re an artist, like a painter. You’re really creating something from your heart that you want to bring pleasure to someone, but you really only have 15 minutes to do it before they start getting really upset. It takes 20-25 to really do it right, but you have to do it in a manner in which they will be patient enough to wait,” Alison Hero said of a typical night behind the scenes at a restaurant. Especially a popular one like the Silverwater.

“I really believe that you have to actually come from a loving place to do it because I think if you don’t people will taste it, and that’s when they get disappointed. Like you’re just not paying attention to the details. You have to have love in your heart.”

She learned this from her Sicilian grandmother, who first taught her how to make gnocchi, an Italian dumpling. Her grandmother said that if you didn’t have your heart in the right place, they wouldn’t float when they were done. As a kid, she thought it was a cute thing to say, but over the years, she realized it held true.

“You really have to put yourself in the right frame of mind to put something out that people are going to catch on the other end, where you’re coming from while you prepared it. It’s hard because on a busy night, we could do 200 dinners in four or five hours. And you’re cooking at least 40 meals an hour, which is what? One minute and 20 seconds,” Hero said

“It’s like you’re in an Emergency Room painting art. It’s just the highest energy. You can’t take a break. You can’t make a mistake or it sets everybody off. But there’s a rush to it I’ve never experienced when it goes right.”

The Dishwasher’s Special

Alison Hero, née Perry, grew up here from middle school on, graduating from Port Townsend High School. Her professional cooking career began at age 12. Later, while working at The Fountain Café, she met David Hero, a potter and commercial fisherman.

“I used to eat breakfast there, and she was the lunch cook,” David said.

Pete Gillis worked with Alison in those early days at The Fountain. He was in high school, working as a dishwasher, while he watched Hero woo the talented chef who was by now in her early 20s. Later, Alison and David married. By the time Gillis came back from college, they’d opened the Silverwater in its original location near the old ferry dock, and Gillis went to work for them there as a prep cook.

“She was very particular about how she wanted her vegetables. I learned a whole bunch of things from David and Alison.” Gillis said.

The first space, by all accounts, was funky. Nothing matched. Not even the hand-thrown ceramic dishes David made. He did, after all, study sculpture and ceramics at Carleton College in Northfield, MN, before he arrived in Port Townsend.

If you walked into the restaurant as a stranger, you wouldn’t be for long. In the earliest days, David’s income from commercial fishing helped out because people weren’t flocking to Port Townsend as they are now, especially to eat. Northwest cuisine was only just starting to catch on. For Alison, those first five years meant 16-hour days, 100-hour workweeks.

At the core, though, regular, local customers were, and are, the restaurant’s raison d’être. In her missive, Alison names off Russell Brown, Ed Louchard, Theresa Fitzgerald, Donn Tretheway, Joe Wheeler, Steve Habersetzer, and Jim Alden, some still with us and some long gone, as those who were the ones they could count on to show up for them in the beginning in a variety of ways. The staff grew to 10 people.

The “boat builder’s special” was $3.95, but David’s favorite dish was something that wasn’t ever on the menu, a dish they came to call the “dishwasher’s special.”

“When we first started the restaurant, I was also the dishwasher, at least for a significant portion of the time,” David said. While the menu had peppercorn chicken served over fettucine, the “dishwasher’s special” featured the peppercorn chicken chopped, tossed with sauce, and served over rotini.

“That was what I had for dinner most of the time,” he said.

Alison narrowed her favorite Silverwater entrée down to two things.

“I really love cioppino because you can use all of the seafood that’s from around here all in one dish,” she said.

While at the old location, she recalled, she received a letter from Bon Appetit magazine asking for her cioppino recipe. At the time, the magazine had a feature where readers could write in to say they loved a particular dish at this restaurant, so please try to get the recipe. Ultimately, they didn’t publish it, but Alison was pleased they even asked for it.

“The second thing is salmon because it’s incredible here. It’s just the simplest thing, and everybody loves it. We use Cape Cleare salmon. That’s the only one we have ever, ever used.”

The Renovation

Imagine the beautiful front windows of the Silverwater closed up with stucco painted lime green. That is how Alison and David Hero found the building when they purchased it for the restaurant five years after their funky beginning in 1989. Their new space, called the Elks building, was built 100 years earlier in 1889 for $18K.

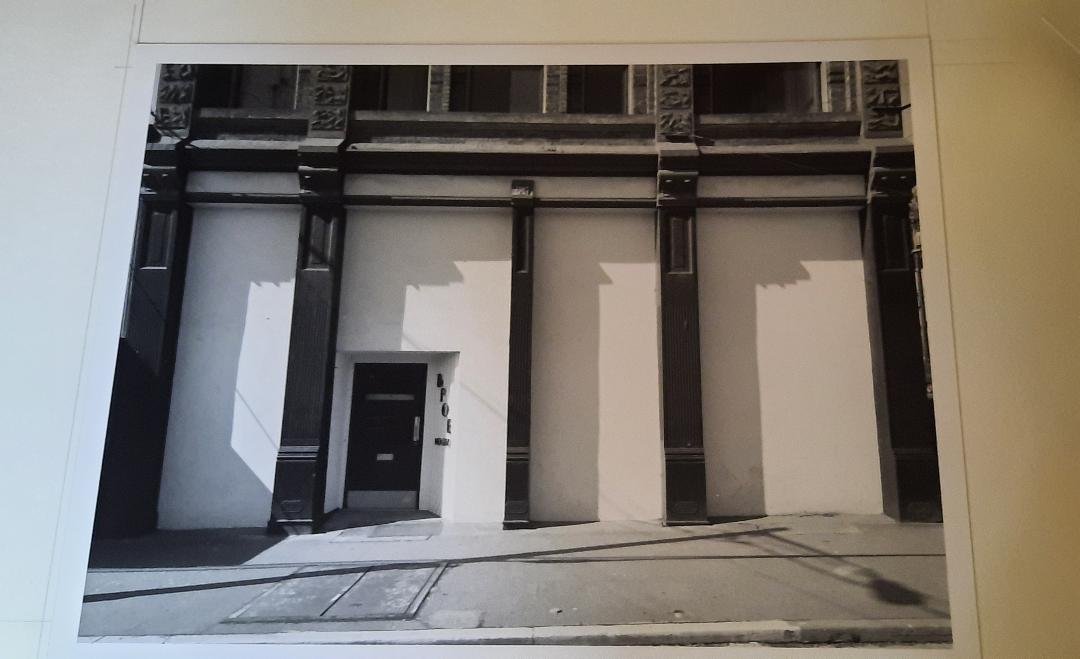

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1080"]

The Elks Lodge closed up the street-level windows of the building in favor of putting in a bar and dance floor. Photo courtesy of Alison Hero [/caption]

For a couple of years before the Elks took over the entire building they’d built for their lodge, the ground level operated as a grocery store. The Elks eventually decided to put a bar on the street level; for privacy the windows were removed.

When the Heros came along in 1994, the Elks had moved out of town. A boarded up building in downtown Port Townsend was not an uncommon thing, but downtown was experiencing a bit of a renaissance, learning what it was capable of being. Rocky Friedman, the original owner of the Rose Theatre, did his own renovation with Phil Johnson, and had opened that movie venue next door in 1992. Port Townsend, the City of Dreams, was having a growth spurt.

“If you think about it,” David Hero said, “[Back then] there were hardly any restaurants in Port Townsend. Now there’s a restaurant every other store.”

Five years after opening in their original location, the Heros and their partners hired contractor Bob Little to build the restaurant of Alison Hero’s dreams, and the lime green came down off of the Elks Building. Regulations required an elevator throughout the entire building. The city’s Historic Preservation Committee had its say in the matter, down to the details of the stained glass windows. The Heros’ were fortunate that they were allowed to do some of the work themselves. Even so, the cost went 100 percent over budget, Alison said.

“David did all of the demolition. He hauled 100 tons of rubble out of here in garbage bags to the dump by himself,” she said.

Solutions appeared as people came forward to help them financially, more than they had expected, and the building was divided into four tax parcels as condominiums. The restaurant moved into the new location in 1996. Their partners owned the upper two floors until the Heros bought them out in 2007.

The renovation also required an extensive retrofit to bring it up to seismic code, later tested by the 2001 Nisqually earthquake. Think steel girders and a lot of concrete.

“It’s one of the safest buildings downtown now. We had an earthquake and nothing happened here,” Alison said. “[This building renovation] was unlike anything else that had ever happened up until that point.”

There were other problems to figure out along the way. David mentioned the pandemic as the most frustrating, of course, but also losing four key staff members at once when they left to start another restaurant in town (The Public House, now The Old Whiskey Mill). Dips in the national economy didn’t help either.

Somehow, they managed to stay solvent. And, while David was no longer the head dishwasher, they both fell into their individual roles that have lasted the course, even if their marriage did not. However, as equal business partners, the two have been each other’s main support all along the way.

“I was the background man, and she was the front of the house,” he said.

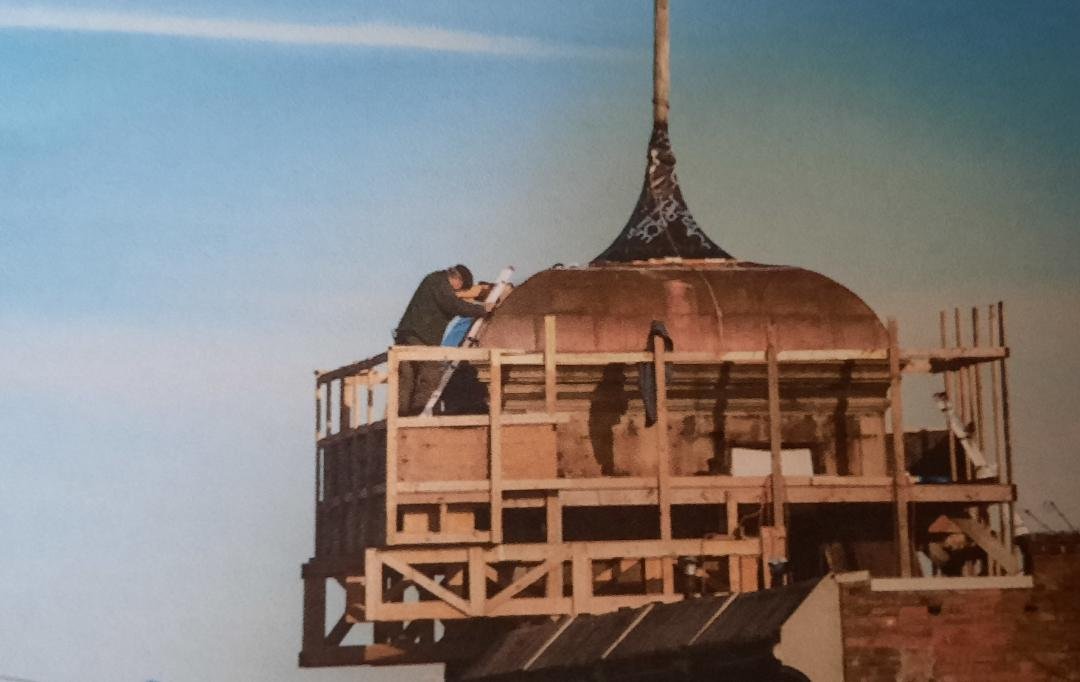

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1080"]

When the cost of a new roof on the building's cupola seemed expensive, David Hero decided to do the job himself. Photo courtesy of Alison Hero [/caption]

Sometimes being the background man meant standing on scaffolding to replace a leaky roof. As the cupola began to leak, something had to be done about the building’s most distinctive feature. A few years ago, David, who took care of what he calls the “physical plant,” considered the options.

“It’s a project that’s really difficult to do because everything’s bent and curved,” he said. David went on to explain that his art background gave him a skill set which could translate into replacing the cupola’s roof with copper, a material that would last two or three hundred years, he decided.

The hardest part was figuring out how to get to the work area.

“I had to do some real fancy scaffolding work up there sticking out the windows in order to make a platform that I could work on,” David said. He made sure it was secure saying, “You could probably park a car on it.”

Despite the problems, even the divorce, neither ever wanted to quit the restaurant. Both went on to embrace each other’s subsequent personal life choices as well.“I don’t know if I can say I ever wanted to quit [the restaurant], but I just didn’t know if I had what it took to keep going. It takes you to your knees. A lot,” said Alison.

David also dismissed the idea of quitting.

“There’s been a lot of times where I was very frustrated and didn’t want to do it anymore, but I can’t say I ever really wanted to quit,” he said. “I think the restaurant has become a significant enough part of Port Townsend that just closing it would not only affect all of the employees, but I think it would affect the community too.

“I always felt like I was going to go until we decided that we could pass it on, and then we would look to find somebody to pass it on to.”

Not all aspiring restaurant owners want to start with someone else’s established eatery though, so the problem there was finding the right person(s). With over three decades each running the Silverwater, both David and Alison wanted to go on to other things, yet they weren’t exactly being flooded with offers.

A Thing For Ducks

Rosscoe Bryant, 34, is from the small coal-mining town of Erie, CO, so he knows what small-town living is like. But he’s been all over the states and has traveled internationally too. Since high school when he graduated from a culinary program, he has trained to step into these shoes.

“He is so qualified for this,” Alison said of the Silverwater’s new owner.

Bryant has a few tattoos like the rest of his generation. He drives a Jeep and has a thing for ducks. He doesn’t look like a restaurant baron. In this town, he could blend in as someone’s kid or grandkid. But, underneath the young man in the newsboy cap, enthusiastic for his first, big challenge in a town where few people really know him, is a dude with a wealth of experience. After high school, he graduated from The Arts Institute of Salt Lake City with a degree in baking and pastry. Then came sushi-making in Japan; fancy restaurants in Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Dallas, Seattle, etc.; and, most recently, commercial fishing in Alaska during the summers while working as a chef at the Suquamish casino the rest of the year.

[caption id align="alignnone" width="486"]

Rosscoe Bryant, 34, brings culinary experience to the Silverwater dating back to his high school years. David Hero has turned over the dessert menu to Bryant who graduated in baking and pastry from The Arts Institute of Salt Lake City Photo by Kathie Meyer [/caption]

He met the Heros last year when his aunt inquired about buying the building as part of a deal that included the restaurant, which Bryant would run. The building was later sold to Buster Ferris of Edensaw Woods; however, the Heros saw potential in Bryant, perhaps something of themselves when they were once young, and continued talks with him about the restaurant sale.

Finally, Alison contacted him to say, “You gotta do it. You gotta figure out how to make it happen.”

Eighteen weeks after he took over, Bryant seemed relaxed and happy in his new role, and was feeling good about the direction things were going.

“From the office I could hear the morning crew singing at the top of their lungs together, nobody in tune,” he reported when he sat down for his interview.

While Executive Chef Adrian Hackman, 35, hasn’t been in the position long, he’s a longtime employee who has worked at Silverwater since he was 17 or 18. His quiet demeanor is appreciated by Bryant and the people who work for him, Bryant said.

“He’s going to keep that continuity from what it was to what it’s becoming,” Alison added.

Bryant plans to give his staff creative license, as he was once given when he developed a dessert tempura made with cake batter. Since Bryant learned how, and became sold on making pasta noodles with duck eggs in Japan, he thinks he’d like to try a house-made pasta program called “Rosseroni’s Duckin’ Good Noods” someday.

Now, he’s hoping no one notices much difference while he makes the rounds and introduces himself to the regulars, or perhaps calls them up if they’ve not been seen since the switchover, and invites them down to try things out. If you’ve never eaten at The Silverwater Café, think imaginative American cuisine with an emphasis on pasta and seafood. It’s fine dining, yet accessible for a working-class budget.

In keeping with the restaurant's concept, the fish and chips remain. The meatloaf, pot roast, and all-you-can-eat spaghetti nights will also continue as will the spice and tea programs. Bryant gives assurance he plans to honor everything Alison and David have built together. If he really wants to put his own twist on things, there is an undeveloped basement space that speaks to him.

A former Port Townsend resident of many years, Terri Quinlan visited the Silverwater when in town last week, and said it was “the same.” And that was a good thing.

Jason Squire, a well-known waiter who worked at the Silverwater for 15 years until the pandemic, is back once a week working Tuesday lunches. So far, said Squire, Bryant seems really nice and enthusiastic.

“He seems to be invested in making things work,” he said.

Truffles and Clay

Both David and Alison have nearly completed this business transition and are now looking at what’s next in life. David is around for assistance for a few more months. Between now and then, he’s working on “The Book of David,” a masterpiece of the building’s nuances, such as what to do if the fire alarm goes off and other essential information.

After he finishes that task, David plans to return to ceramics and put his education to creative use in sculpture. He’s already traveled to see his college professor’s retrospective, finding inspiration there to move him forward.

Alison, who has already written one cookbook, thinks she might have another cookbook/memoir in her, but mostly she wants to reconnect with her home on a few acres outside of town. Hang out with her chickens and knit. Walk. Tend to fruit trees. The sort of things she didn’t have time to do before. She is also available for Bryant for the next few months.

While Alison is intentionally not making plans at the moment, she has applied for a spot on a truffle-hunting expedition in Croatia next year. Eventually, when more details are nailed down, a party is being planned for the local community to celebrate what the two have achieved.

Whatever they do, no doubt it will be done with a full heart.