The Intersectionality of Grief: Notes from Next to the Bed

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1175"]

Trucker Hat Painting by Meg Kaczyk [/caption]

By Angela Downs

Meg and I met in early spring at Art Lab Thuja, a contemplative art practice off of Center Road. She was working on a graphic novel about her experience as a caretaker for her husband with terminal cancer who died last year. When I reached out to Meg for an interview, she invited me to her art studio for our conversation. She welcomed me into the basement level of her home, once a shared workspace with her husband Joe, now an expanded painter’s studio. We began with her new book.

“The book is obviously about grief because it's the process of someone dying. But this work is less about grief and more about intimacy and the privilege of caregiving. The last chapter of the book is called Courage. It's the wonder of that. We're all going to die. How do you approach it? And then how is caregiving hard, easy, joyful, all the shades of everything? I felt like caregivers needed to have that reflected back to them.

It wasn't until after he died that I really started putting together a narrative, though this notion of daily practice started in Seattle when we were at what I call, The Cancer Hotel, which was patient housing for Fred Hutch. I decided, I'm going to have something to do here for two and a half weeks while he was in radiation, and so I went to Blick and randomly picked some medium I hadn't used before. So every day, I would walk to the store or walk around the neighborhood after I had cared for him, and I would snap pictures, come back to the hotel, and work on a drawing that day. My goal was to fill the sketchbook while we were there.

While he was in the cancer hotel, he got approved for the end-of-life medication. We came home and I was very aware that everything we were living was so precious, even the most ordinary things, so I made a sketchbook called Everyday Ordinary. After the time in Seattle, there was a bit of a respite. I had more time in the studio, but once things got really rough again, I started this book, Messy. Grief is just messy. It's not a perfect circle. This book was everything I saw in life or around us that was not binary, not black and white. By this time, things were really bad15 minutes a day was all I had, and so Messy finished near the end. From this point there was no art making. It was full-on just being with him. That is how I started the daily practice.”

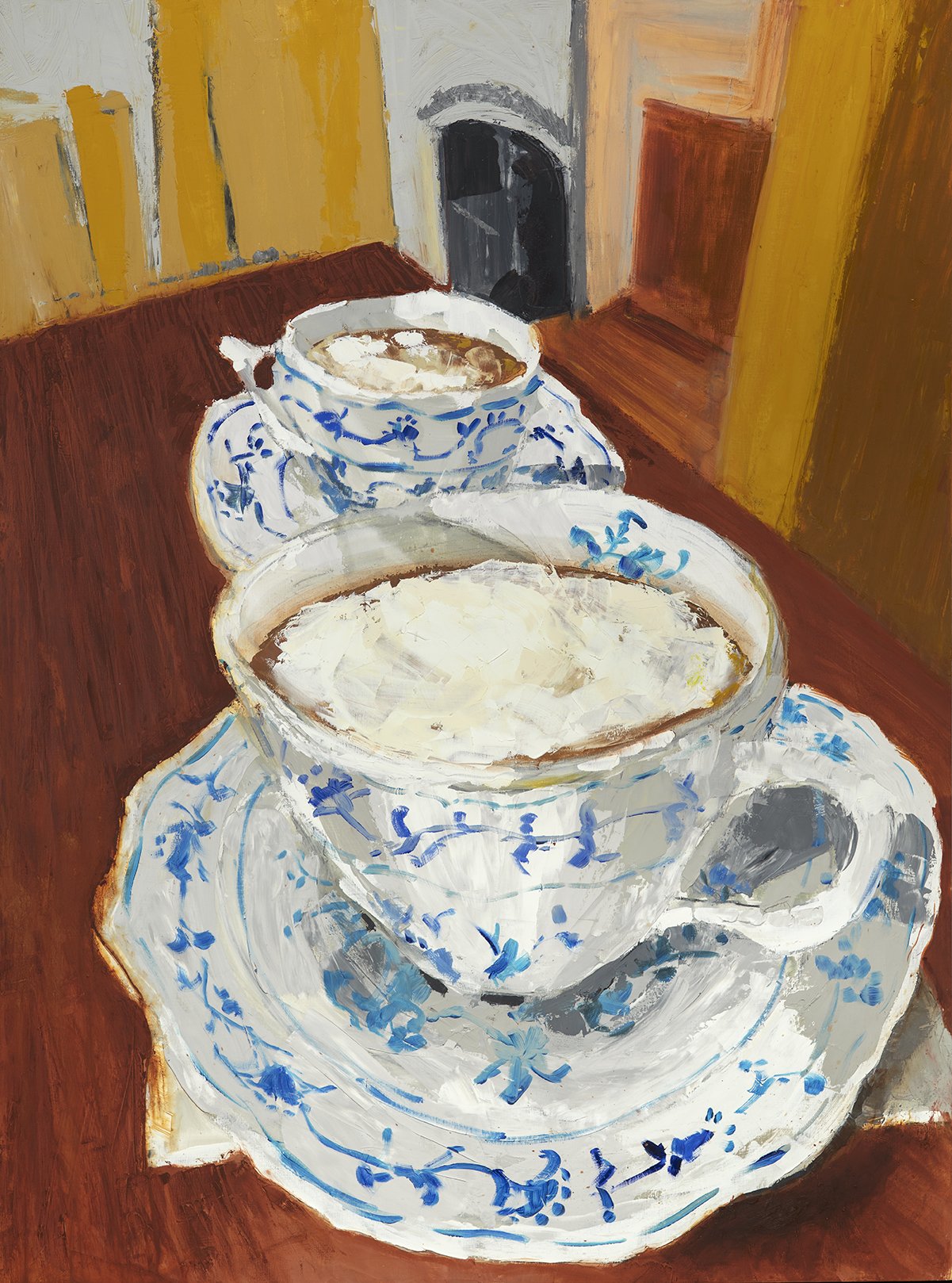

Standing in Meg’s studio, her work surrounding us on the walls, I could feel the depth of love like a transmission from the paintings. His chair, the series of swirling lattes in teacups, the hospital from the outside, detailed wounds, a six-foot naked man moving away towards a world beyond this room, all quietly infused in me a sense of profound loving acceptance as Meg spoke.

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1201"]

Two Cups Painting by Meg Kaczyk [/caption]

“I loved his ass. I needed to do a life-size nude of him. I didn't know it was going to turn into work; I didn't even know if I was going to like the painting, I just knew I had to do it. It was very much cathartic grief. And then I also put together this timeline of his disease. It helped me because I could see tumors, him on a trial drug, drugs working for maybe a year and a half, trial drugs started failing, radiation. Because he did Death With Dignity, I needed to feel—I supported him always, whatever he wanted, but I just needed to know that it really was time, he had chosen it, and it really was time. Most people fight cancer to the bitter end; if you were going to do Death With Dignity, you wait until there’s no hope. Joe didn't want to go when he was down at the bottom. When he was ready, we were actually able to sleep in the same bed for the last two nights, which we hadn't been able to.

After we'd come back from Seattle, I did free writing, and then I put it away because life got real. So after he passed, I pulled that writing out of curiosity, and I was stunned by how raw I was at the time I was writing it. Then I got out my journals. There's something going on here. What is it? A friend said, “Well, how about a graphic novel?” When this turned into more of a project, it really helped me to have something to focus on that had shape, form, vision, and purpose with forward motion. The development of something into something else. Personally, having this gave me a strong sense of service around the purpose of the book for other caregivers.”

The contraction and expansion of Meg’s lived experience was part of the privilege of caretaking at such depths, and I was amazed by her innate intelligence to ask to be witnessed as a Witness, following her body’s wisdom of good timing.

“I sat in the bathroom, his feet had a lot of open wounds on them at one point, things moved around, and I was washing his feet– it's kind of funny because he was not a Christ-like figure, nor am I particularly Christian– but I'm washing his feet, and I couldn't help but think of Jesus and the disciples, and I was laughing. I'm like, you know, it's my honor to serve you. It just seemed so classic. It was kind of around the time I did the painting of the tumor on the back of his head. I would take a palette knife, dip it in the aquifer, and put it on to cover the nerve endings. I was a master at it; nobody did it like me. His sister loves that painting because of the idea that I used a palette knife to paint it and yet that was what it was like caretaking. It was an art form, really intense, and not easy.

He would be in so much pain; I see the wounds, and I would feel it in my body. I would take in the pain, viscerally, it would be in my heart, in my body. I usually kept it to myself because it's hard for him to know that I'm feeling that. But occasionally, I couldn't help it. I'd either cry, or I would sigh,or some verbalization would come out. He would feel so bad he would make a joke. “Oh, it's just a flesh wound.” He would try to cheer me up. But I wanted to hold my own pain. I didn't want to pass it on back to him. It's great emotional courage that he had, but also me. I think that's where art making helps, and journal writing. When he passed he made noises, which I was told and reassured that he was not in pain, but it was really hard. I thought, “Oh my God, one more time, I have to sit and just be a witness and just hold it.” I think the process of grieving and perhaps writing the book, meditation, physical exercise, taking really good care of my body– it's going to be a process of that held pain coming out.

There is a tendency at first to try to hurry through. One of my post-Joe passage books is called, Emergence. I think that was premature. I'm learning I don't have to define anything. I don't have to emerge. There's nothing I need to do to make any changes. This would be true for anyone who broke up with someone, not just loss in death, but of any dynamic relationship. You’re not going to be who you were before you met. I have been changed by him. I'm not going to be who I was with him because there is what we call the third candle; there's the person, you, and your relationship. That third candle died with him. So who am I?”

Book Launch Event

Notes from Next to the Bed: A caregiving love story in words & pictures by Meg Kaczyk

Friday, September 27, 6-8pm • Sunrise Coffee, Port Townsend