The Intersectionality of Grief: Whaling

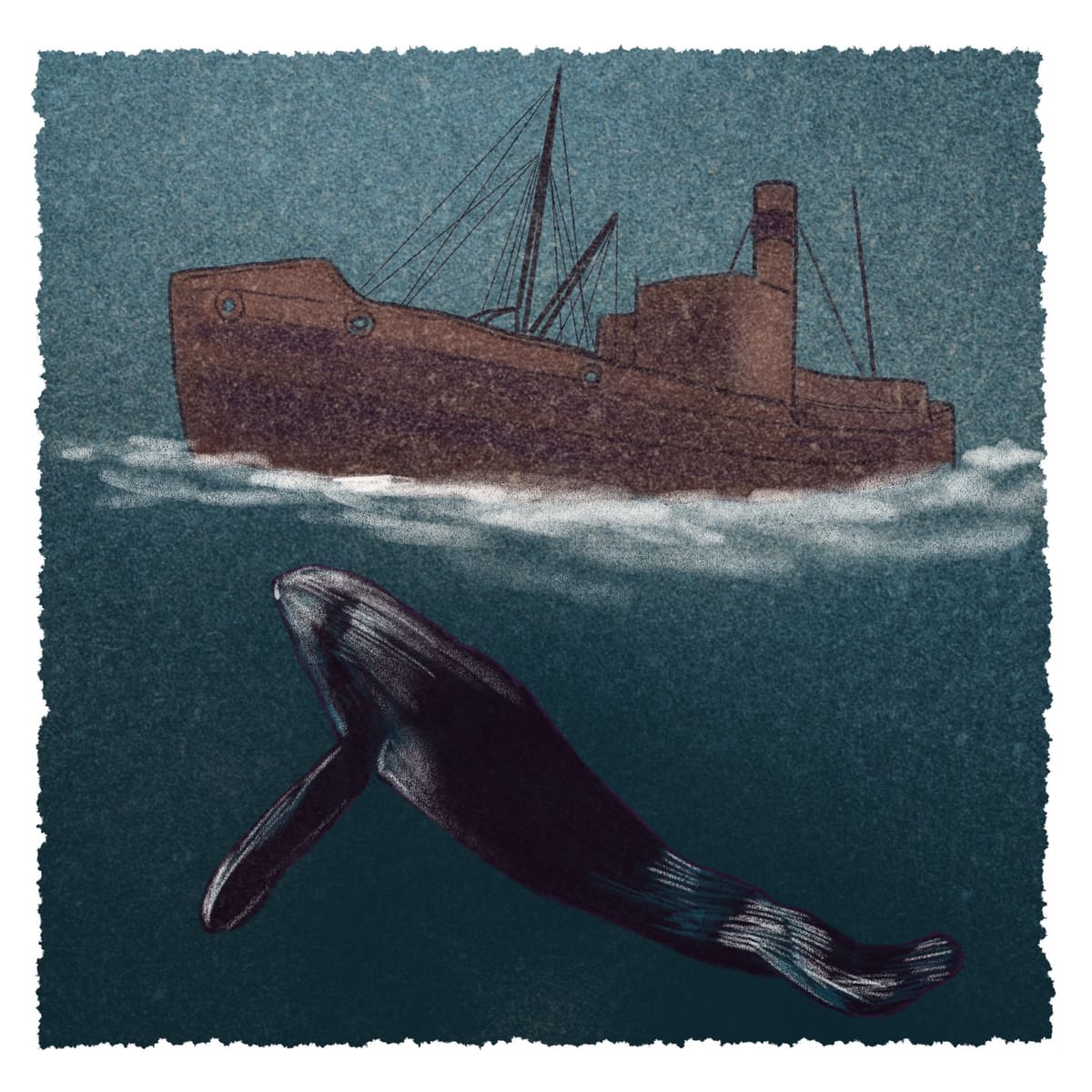

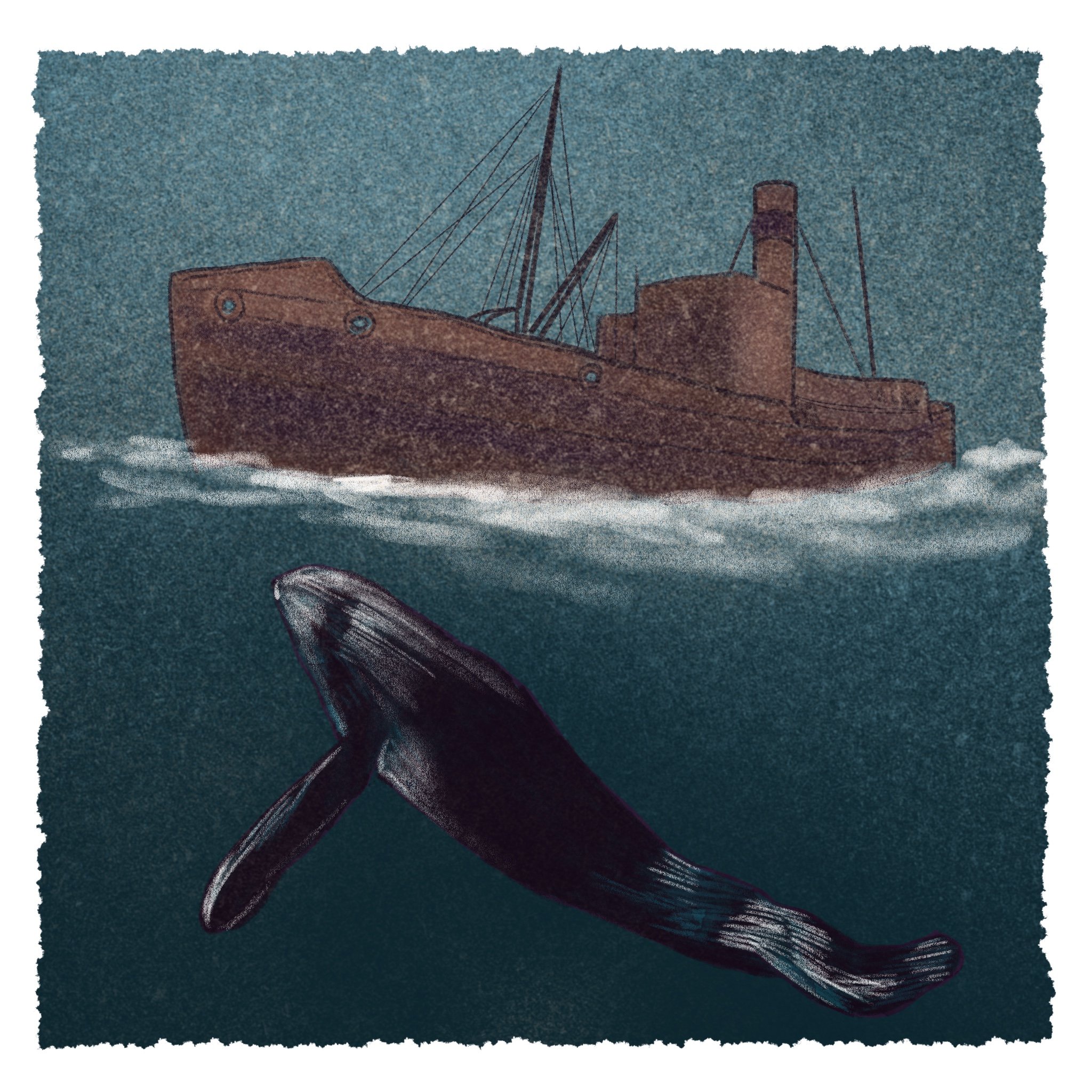

[caption id align="alignnone" width="2048"]

Illustration by Nhatt Nichols [/caption]

A Grief Column by Angela Downs

Many do not consider the more than human to be our community members, that these relationships are not worth fortifying and mourning. Often lacking the tools to challenge our predispositions, it is common for us to live with deep, unknown and unexamined grief.

When I was in my early to mid-twenties, I adopted the belief that I had a duty to society to absorb the healing responsibility after an illness of the spirit and educate myself about the lineage I’ve come from. I learned I follow generations of whalers. For six years, I have oscillated between outpourings of pain for what my people have done, and gratitude for their bravery, skill, and fortitude.

I recently watched Whale Hunters: An Untold History. It briefly covers early whale hunting but focuses on the turn of the century and industrial whaling.

In the mid-19th century, British whaling almost ended because of the near extinction of the Right whale, called so because they were docile, moved slowly, and after they'd been killed, they floated. After a couple hundred years of exploitation, they were essentially driven extinct in the North Atlantic. The blue, minke, fin, and sei whales were abundant but were too fast to be approached by sailboats and rowboats, and if they were harpooned, they sank.

It was in these long-ago times the images of family whalers played their dramas in my mind. The name Nickerson was on the Essex in 1819, but images of the Nickersons whaling in Nova Scotia in the winters of the 1930s-1950s and traveling back down to the factories in Massachusetts in the summers were less romantic.

Sven Foyn, the mind of modern whaling, invented the whale catcher, a harpoon cannon mounted on steam-powered ships, and designed a hypodermic needle-like apparatus for pumping air into the species that sank so they floated and could be collected later. No whale could escape.

I’ve held resistance to the acceptance of more recent history. The intensity of greed the industrial revolution brought and the distortion of needs capitalism hypnotized into the public remain wounds my fantastical self seeks the antidote for all.

With the advent of explosives and steam, the Humpback, in particular, was in steep decline. From something like 5,000 whales in 1910, it dropped to 474 only three years later. When the First World War broke out, whale oil was in even more demand for the manufacture of nitroglycerin in explosives.

To save whales, you had to kill them. They figured the science of the large whales depended upon whaling. With attempts at establishing regulations underway and hunting grounds shrinking, factory ships were developed as completely self-sufficient units that could go wherever the whales were. This was called pelagic whaling and allowed the industry to escape regulations.

With new science, pressure from anti-whaling activist groups, and the growing popularity of vegetable oils, whaling was finally banned in 1966. 1.6 million whales were killed in 55 years of whaling operations in Antarctica alone.

We now have access to current tools allowing us to not only track migrations, hunting tactics, breeding habits, and closely watch whale populations’ sensitivity to toxins, changing temperature, and military underwater trial explosives but also to potentially decode the whale’s languages.

A grandmother whale might be so generous someday to share her stories of community resilience, their rituals, and the connection between deep water and dry land. We are not taught to seek the spirit in our resources. And while we may attempt sustainability, we are still extractive. Will we be able to receive the wisdom we so desperately need? And the self-discipline to slow down and adapt to technology with grace?

Many businesses today were started on money earned at whaling, and many lives were saved and supported. Who knows which of us wouldn’t be here today without it? My grandfathers were the laboring men, drenched in the sacred oils pouring from their blades. My fathers built our homes.

Still, I struggle with the wounds of industrialization, affecting every living thing. I mean to offer permission to those who may need it, to grieve for the more than human, and to remind us that gratitude is a companion of grief. It is our response to technology that informs the web of relations we live in.