The Rental Market has Been Taken Over by Short-Term Rentals. Is it Time They Helped Provide an Affordable Housing Solution?

News by Rachael Nutting

The picture is postcard-perfect: a charming cottage, a sleek condo with a mountain view, a cozy bungalow, steps from the beach. For travelers, short-term rentals (STRs) rented by platforms like Airbnb and Vrbo offer an authentic, home-like experience. For property owners, they represent a lucrative revenue stream, often far exceeding long-term rental income.

But in tourism-dependent communities like Port Townsend, this economic boon has a profound and painful flip side: it contributes to a full-blown housing crisis that is displacing the very workers the industry itself needs. For Washington towns grappling with this challenge, a new state legislative tool offers a path toward balance and could be a turning point in 2026.

Washington's short-term rental market is a significant economic engine. It’s estimated that the state’s STR market generated $4.7 billion in 2024. Many defend STR rentals as a way for senior citizens to rent a vacation room in their homes, using the extra income to cover their housing costs. However, the vast majority of STRs in Jefferson County are entire homes (73% in Port Townsend and nearly all in unincorporated areas), representing housing units removed from the long-term rental stock.

This dynamic—profitable STRs squeezing an already tight housing market—is not unique. Research confirms that increases in STR listings are associated with rising rents and a decrease in the supply of long-term rentals nationwide, as reported by The National Low Income Housing Coalition. The effect is often most acute in desirable, tourist-friendly neighborhoods.

Jefferson County exemplifies the struggle between economic benefit and community preservation. On one hand, STRs support a vital tourism economy. Existing lodging tax funding is distributed through the city and county’s Lodging Tax Advisory Committee (LTAC) for tourism events like the Wooden Boat Festival and the Port Townsend Film Festival, which bring in millions in direct visitor spending.

[caption id align="alignnone" width="1264"]

Permitted STR operations throughout the county in 2025, image from Jefferson County website [/caption] [caption id align="alignnone" width="1246"]

30-day rentals advertised on Airbnb within city limits, 2026 [/caption]

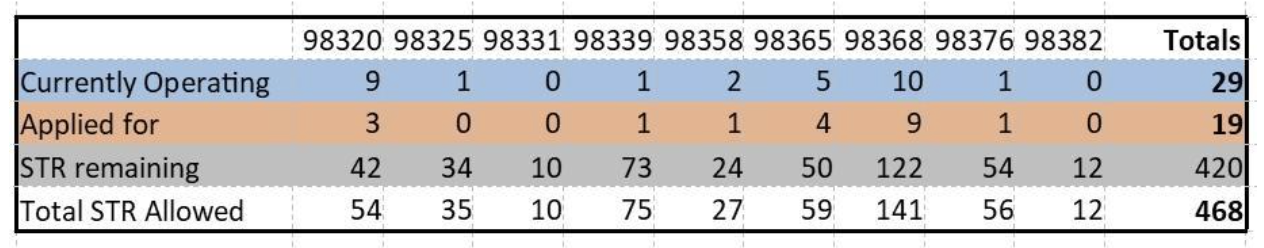

The county has taken regulatory steps, enacting an ordinance that caps STRs at 4% of dwellings per zip code and requires all operators to obtain a permit within 6 months of April 2025, excluding Master Plan Resorts.

However, enforcement is a critical weakness. As of January 2026, Commissioner Greg Brotherton noted that only 9 of the estimated 400-500 non-permitted rentals had come into compliance, a task made more difficult by recent cuts to code compliance staff. New regulations cap the total of allowed STRs throughout the county at 468.

The city of Port Townsend added strict regulations on STRs in 2017 and grandfathered in around six STRs. Data on the City of Port Townsend's website showed twenty-six permitted STRs as recently as 2024, though Air DNA , an online service that compiles data from Airbnb and Vrbo, states there are 224 properties within the zip code.

The Legislative Response: Turning STR Revenue Into Housing Solutions

In response to crises like Jefferson County's, Washington lawmakers have proposed a targeted solution: Senate Bill 5576. This bill, currently in the state legislature, would empower counties and cities with a new tool.

Key Provisions of SB 5576:

· Authority: Allows local governments to impose a special excise tax on STR lodging.

· Tax Rate: Up to 4%, applied exclusively to short-term rentals.

· Revenue Use: Funds must be used for affordable and workforce housing programs. This includes acquiring, rehabilitating, or constructing housing; providing rental assistance; and funding supportive services.

· Accountability: Requires local governments to publish an annual public report on how the revenue is spent.

For Jefferson County, the financial potential is significant. Data from Air DNA shows Jefferson County’s 411 active STRs generate an estimated $17.5 million annually. A potential 4% tax on that activity could produce around $702,668 dedicated to local housing efforts.

Fears of an additional tax harming tourism are prevalent, though those fears turned out to be unfounded in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, another region that has a strong tourism economy.

In 2019, a state STR tax of up to 6% was imposed. Over the following three years, this generated just under $25 million in state funds that locals could vote to allocate toward affordable housing and local infrastructure.

Fast-forward to 2025, and Massachusetts cities were still struggling to manage STR growth from overtaking residential housing stock, demonstrating that the additional tax did not noticeably affect tourism.

The Path Forward: A Multi-Pronged Strategy for 2026

SB 5576 is a powerful potential tool, but it is not a silver bullet. Solving the housing crisis in communities like Jefferson County requires a coordinated, multi-pronged strategy.

First, it must include the enactment and enforcement of smart regulation. For SB 5576’s tax to be effective, it should work in tandem with the county's existing permit cap.

However, regulations are meaningless without enforcement. Recent budget cuts to county compliance staff hinder efforts to bring the shadow market of hundreds of unpermitted STRs into the light, reclaim potential housing, and capture all due revenue. Proper enforcement capacity would need to be reinstated for SB 5576 to truly work.

This regulatory effort should be paired with efforts to secure complementary funding. Commissioner Greg Brotherton has highlighted House Bill 1867, which would allow counties to ask voters to approve a Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) for affordable housing, similar to San Juan County's successful model.

San Juan County voters approved a 0.5% REET tax in 2018, and it has since directed over $15 million towards affordable housing. Though the revision to this bill that would allow Jefferson County to use this tax has not yet passed, such a measure would provide another crucial, dedicated funding stream for local housing initiatives.

Ultimately, housing advocates argue that the community must also embrace creative housing solutions. This includes backing specific projects like Community Build’s Tiny Homes on Wheels (THOW), advocating for regulatory reforms to allow more diverse housing types—such as accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and middle housing—and accepting the necessary density to allow growth through updated comprehensive planning. They believe that only through this combined approach of enforced regulation, dedicated funding, and community-supported innovation can meaningful progress be made.

The choices made by state legislators in Olympia, and by local leaders and citizens in communities across the Olympic Peninsula, will determine whether this moment becomes a turning point. The path forward requires moving beyond seeing STRs as either a villain or a savior. It demands recognizing them as a powerful economic force that must be intentionally managed. The goal is a calibrated model where tourism supports the community without consuming it—where there are homes for the people who make the coffee, serve our food, teach the children, and keep the heart of the destination beating, long after the tourists have gone home.